Interview: Tessa Strickland, Publisher

Posted on May 17, 2017Together with Nancy Traversy, Tessa Strickland founded the award-winning independent children’s publishing house Barefoot Books in 1992 as part of a dream to live differently, moving away from a corporate London career to create a small business where imagination could thrive.

Barefoot Books opened a New York office in 1998 and has published hundreds of books for children, translated into over twenty five languages, and sold millions of copies internationally. The stories range from fiction to non-fiction and new to traditional, but they all celebrate education, a love for the Earth, and a connection between all communities.

In December 2016, Strickland stepped-back as the editor-in-chief, but after 25 years at Barefoot this is by no means the end of her career. Under the name Stella Blackstone, Tessa has authored over 60 children’s books, including titles such as A Dragon on the Doorstep and Bear on a Bike, and now devotes her time and expertise to writing for both children and adults, as well as working at her private physiotherapist practice.

A Dragon on the Doorstep illustrated by Debbie Harter

Although Strickland doesn’t illustrate any of her stories herself, she grew up with a love of painting and has a keen eye for matching illustrative styles with the right story. I’ve been lucky enough to ask Strickland about the illustrative side to children’s literature. To begin with I asked what she considers her favourite illustrated book, and unsurprisingly the answer is “I don’t think I can limit myself to one favourite. Well, I know I can’t.” Instead she notes that it is never purely the illustration which will establish a book as a favourite, rather that it must be a balance (“it is the way the illustration and the design and the narrative all work together”), before going on to name a few of her most treasured books.

First on the list is Astrid Lindgren’s The Tomten, illustrated by Harald Wiberg. This is the story of a Scandinavian dwarf-like creature and his night-time walk around a snowy farm. “The Tomten reassures all of the animals that they are safe, and he talks to them in Tomten language, which horses, cows, cats, children etc understand.” Tessa notes how Wiberg uses beautifully soft images to depict this amazingly comforting story. “The illustrations are very restful to look at, in a way that compliments the text.” It is easy to see why this book may be the perfect bedtime story. “The implication of this classic picture book is that someone special is out there, even in the dead of night, and this someone likely understands you, the child, even if your parents probably don’t.”

In Strickland’s childhood favourite, A Child’s Golden Treasury of Poetry by Louis Untermeyer, she describes how pictures can be used as a gateway to a different kind of reading: “it’s a fantastic example of the way in which illustrations can make a book accessible to a child.”

In Claire Nivola’s Orani: My Father’s Village, the illustrations act as a a window with which the reader can share in the memory of a far away place. “Memories of summer holidays in her father’s Sardinian village evoke an entire way of life in the Mediterranean. Whenever I pick up this book, I find myself led into the bright light and dusty streets of the village.”

Finally, Strickland touches on some more contemporary favourites, and suggests less is often more: “I think Chris Haughton’s book Shh! We Have A Plan! is a stunning exercise in graphic self discipline and so are all of Jon Klassen’s books. They are pure genius.”

As for her favourite Barefoot book, Strickland chooses The Barefoot Book of Children. “Every double-page spread in this one-off look at the different ways in which children across the world live their lives is a masterclass in itself. All of them take my breath away, but I particularly love the one which shows different children at bath-time. Thank you again, David!”

I then asked Strickland, as a publisher, what she looks for in an illustrator’s portfolio. Her answer is threefold: originality, discipline and presentation. “To be original is perhaps the most elusive thing and yet the most obvious, because all we need to do to be original is to be ourselves,” she explains. She adds, “one of the hardest things to find, as a publisher, are illustrators who know how to draw children and who can retain and develop a sense of character throughout a story.” She also gives a wise word to consider when choosing a story: “there’s a powerful push-pull in picture books that it pays to bear in mind: children love to be scared but at the same time, they need to feel safe, certainly by the end of the story.”

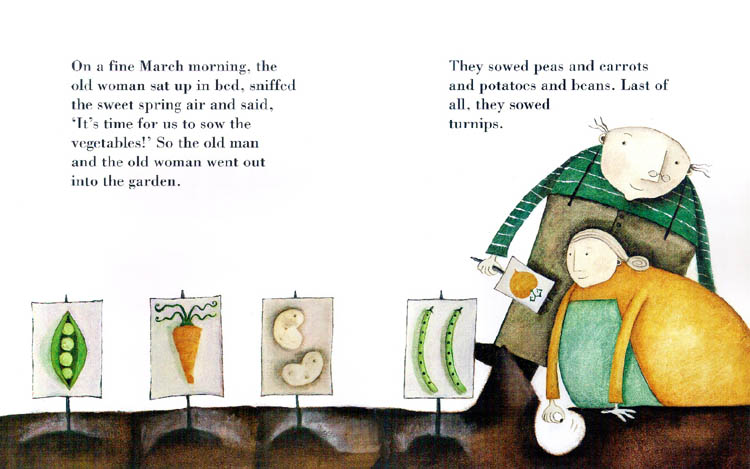

As for discipline, Strickland looks for consistency as well as a true ability to understand a text. “To illustrate well you have to have a sense of how to tune into the emotional messages of the text and to draw these out by changing gear in the right way at the right moment. Niamh Sharkey does this to brilliant effect in The Gigantic Turnip, which has been translated into 26 languages and counting.”

Strickland describes how essential it is to have an awareness that presentation matters: “it shows the publisher that you take pride in your work and that you know how to organise yourself as well as knowing how to express yourself creatively. Of course, presentation alone is not going to get you a commission – you have to have the talent as well – but it is well worth taking the trouble to think through what you want to present and how you want to present it.”

As a final word of encouragement to all aspiring illustrators, Strickland reminds us to keep a thick skin and not give up – self belief is key! “The selection process is subjective too – what is not quite right for one publisher may well be pitch-perfect for another. Believe in yourself and believe in your work and you are already well on your way!”

Words by Katie Williams

Featured image from The Barefoot Book of Children, illustrated by David Dean